A Bird Without Wings

In the mid-1920s, aviation in New Zealand was still more promise than reality. When the Government signalled in 1927 that it intended to support private aero clubs—by supplying training aircraft and subsidising qualified pilots—Otago’s aviation enthusiasts didn’t wait to be invited. They moved first.

Even before the policy was formally announced, a small group set about forming what would become the Otago Aero Club (OAC), determined to meet whatever conditions the Government might impose. Watching Britain and Australia actively foster civil aviation, they fully expected New Zealand to follow suit. The Club’s secretary, H. A. White, wrote to the Defence Department for guidance and was supplied with the regulations of the London Aero Club. Using these as a blueprint, the OAC quickly became a properly constituted organisation on the 21st of January 1927 —arguably the best-prepared aero club in the country.

Then they waited.

For more than a year the Club pressed on with meetings, lectures, and planning, confident that official recognition would follow. Instead, in April 1928, the Government announced that the first four DH Gypsy Moth aircraft would go to Auckland and Canterbury—two each. Otago received nothing, despite widespread opinion that the OAC was the only club that fully met the stated requirements.

Worse followed. The Minister of Defence publicly denied that any promise of assistance had ever been made. He claimed no knowledge of the Club’s membership, instructors, or even a suitable aerodrome in Dunedin. For Otago’s aviation pioneers, it was a stinging rebuff.

They responded forcefully. On 18 April 1928, a deputation of 20—representing both the OAC and the Otago Expansion League—confronted the Minister at the Grand Hotel. White laid out the Club’s efforts and frustrations, memorably likening their situation to “preparing a stable before there was any chance of getting a horse.” Without an aircraft, progress was impossible; with one, an aerodrome could quickly be secured.

The Minister softened. He admitted aviation expertise was thin in New Zealand and explained that policy decisions had been delayed while Captain Isitt studied developments in Britain. Auckland and Christchurch, he said, had been favoured simply because they already had aerodromes and facilities. If Otago could provide the same, its application would be considered—and any proposed site would be inspected without delay.

From that moment, momentum shifted.

Membership climbed steadily, public interest grew, and by late 1928 aircraft were visiting Dunedin regularly, drawing crowds and civic leaders alike. Women joined the Club. Donations flowed in. By 1929, membership had passed 100 and the Club’s finances were strong enough to order its own aircraft.

Fundraising reached a dramatic peak with the “Golden Wings” Art Union, launched jointly with the Canterbury and Southland Aero Clubs. Offering thousands of pounds’ worth of alluvial gold as prizes, it proved phenomenally successful, raising £17,500—an extraordinary sum for the time.

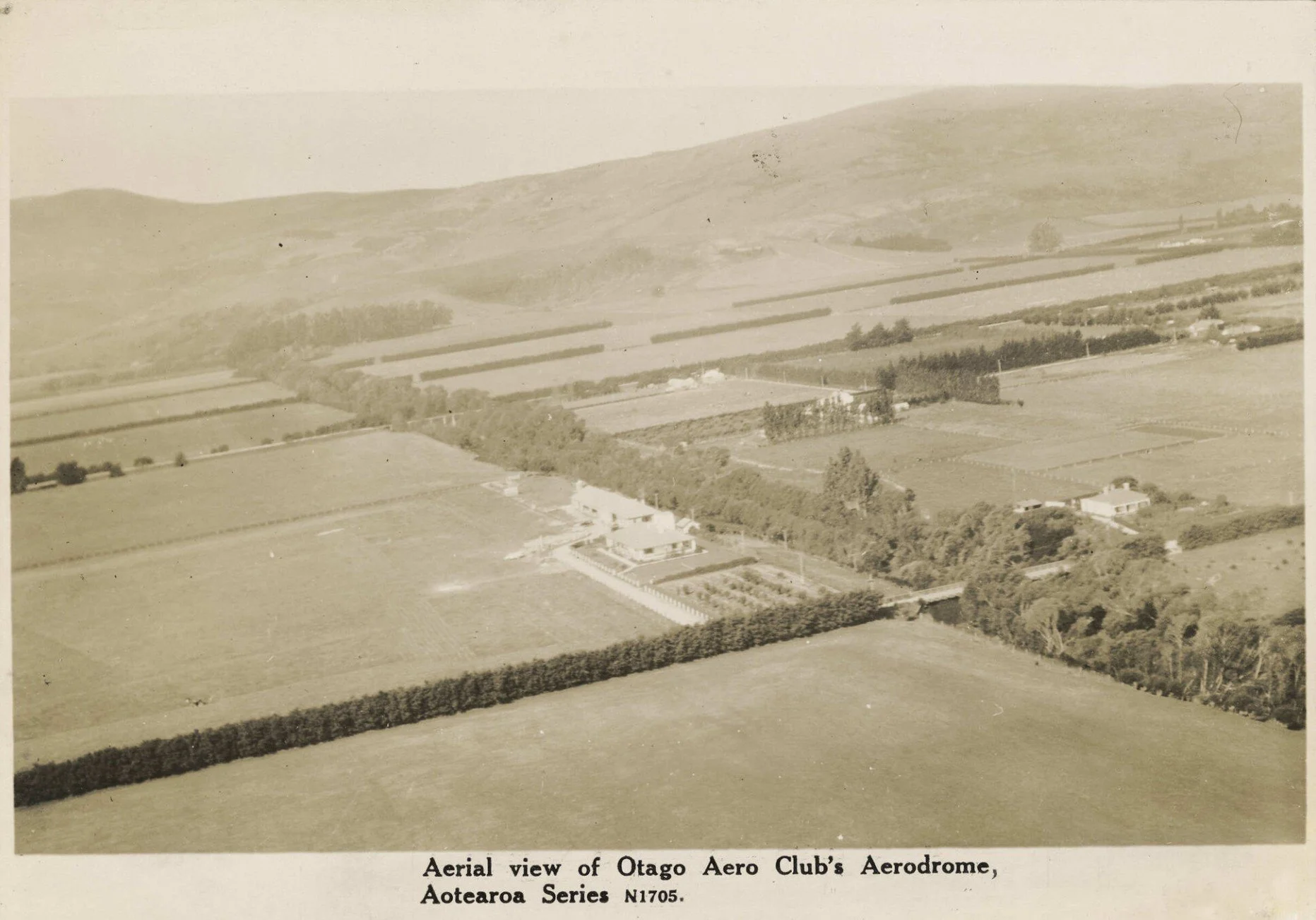

That success made the decisive step possible. In 1930 the Club acquired more than 100 acres of flat land on the Taieri, securing Otago’s long-term aviation future. Government support followed at last: aircraft were loaned, and a pilot-instructor appointed.

On 19 October 1930, Flying Officer E. G. Olson landed a Government-loaned Gipsy Moth, ZK-ABO at Taieri. With that flight, the Otago Aero Club finally moved from aspiration to operation—training pilots, carrying passengers, and taking its place in New Zealand’s aviation story.

Otago Aero Club was a bird without wings no longer.